By George Friedman

The United States is, at the moment, off balance. It faces challenges in the Syria-Iraq theater as well as challenges in Ukraine. It does not have a clear response to either. It does not know what success in either theater would look like, what resources it is prepared to devote to either, nor whether the consequences of defeat would be manageable.

A dilemma of this sort is not unusual for a global power. Its very breadth of interests and the extent of power create opportunities for unexpected events, and these events, particularly simultaneous challenges in different areas, create uncertainty and confusion. U.S. geography and power permit a degree of uncertainty without leading to disaster, but generating a coherent and integrated strategy is necessary, even if that strategy is simply to walk away and let events run their course. I am not suggesting the latter strategy but arguing that at a certain point, confusion must run its course and clear intentions must emerge. When they do, the result will be the coherence of a new strategic map that encompasses both conflicts.

The most critical issue for the United States is to create a single integrated plan that takes into account the most pressing challenges. Such a plan must begin by defining a theater of operations sufficiently coherent geographically as to permit integrated political maneuvering and military planning. U.S. military doctrine has moved explicitly away from a two-war strategy. Operationally, it might not be possible to engage all adversaries simultaneously, but conceptually, it is essential to think in terms of a coherent center of gravity of operations. For me, it is increasingly clear that that center is the Black Sea.

Ukraine and Syria-Iraq

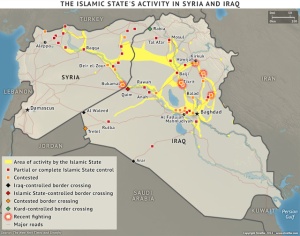

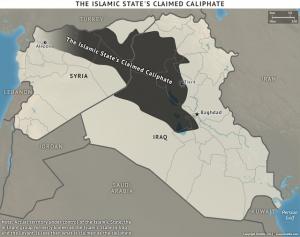

There are currently two active theaters of military action with broad potential significance. One is Ukraine, where the Russians have launched a counteroffensive toward Crimea. The other is in the Syria-Iraq region, where the forces of the Islamic State have launched an offensive designed at a minimum to control regions in both countries — and at most dominate the area between the Levant and Iran.

In most senses, there is no connection between these two theaters. Yes, the Russians have an ongoing problem in the high Caucasus and there are reports of Chechen advisers working with the Islamic State. In this sense, the Russians are far from comfortable with what is happening in Syria and Iraq. At the same time, anything that diverts U.S. attention from Ukraine is beneficial to the Russians. For its part, the Islamic State must oppose Russia in the long run. Its immediate problem, however, is U.S. power, so anything that distracts the United States is beneficial to the Islamic State.

But the Ukrainian crisis has a very different political dynamic from the Iraq-Syria crisis. Russian and Islamic State military forces are not coordinated in any way, and in the end, victory for either would challenge the interests of the other. But for the United States, which must allocate its attention, political will and military power carefully, the two crises must be thought of together. The Russians and the Islamic State have the luxury of focusing on one crisis. The United States must concern itself with both and reconcile them.

The United States has been in the process of limiting its involvement in the Middle East while attempting to deal with the Ukrainian crisis. The Obama administration wants to create an integrated Iraq devoid of jihadists and have Russia accept a pro-Western Ukraine. It also does not want to devote substantial military forces to either theater. Its dilemma is how to achieve its goals without risk. If it can’t do this, what risk will it accept or must it accept?

Strategies that minimize risk and create maximum influence are rational and should be a founding principle of any country. By this logic, the U.S. strategy ought to be to maintain the balance of power in a region using proxies and provide material support to those proxies but avoid direct military involvement until there is no other option. The most important thing is to provide the support that obviates the need for intervention.

In the Syria-Iraq theater, the United States moved from a strategy of seeking a unified state under secular pro-Western forces to one seeking a balance of power between the Alawites and jihadists. In Iraq, the United States pursued a unified government under Baghdad and is now trying to contain the Islamic State using minimal U.S. forces and Kurdish, Shiite and some Sunni proxies. If that fails, the U.S. strategy in Iraq will devolve into the strategy in Syria, namely, seeking a balance of power between factions. It is not clear that another strategy exists. The U.S. occupation of Iraq that began in 2003 did not result in a military solution, and it is not clear that a repeat of 2003 would succeed either. Any military action must be taken with a clear outcome in mind and a reasonable expectation that the allocation of forces will achieve that outcome; wishful thinking is not permitted. Realistically, air power and special operations forces on the ground are unlikely to force the Islamic State to capitulate or to result in its dissolution.

Ukraine, of course, has a different dynamic. The United States saw the events in Ukraine as either an opportunity for moral posturing or as a strategic blow to Russian national security. Either way, it had the same result: It created a challenge to fundamental Russian interests and placed Russian President Vladimir Putin in a dangerous position. His intelligence services completely failed to forecast or manage events in Kiev or to generate a broad rising in eastern Ukraine. Moreover, the Ukrainians were defeating their supporters (with the distinction between supporters and Russian troops becoming increasingly meaningless with each passing day). But it was obvious that the Russians were not simply going to let the Ukrainian reality become a fait accompli. They would counterattack. But even so, they would still have moved from once shaping Ukrainian policy to losing all but a small fragment of Ukraine. They will therefore maintain a permanently aggressive posture in a bid to recoup what has been lost.

U.S. strategy in Ukraine tracks its strategy in Syria-Iraq. First, Washington uses proxies; second, it provides material support; and third, it avoids direct military involvement. Both strategies assume that the main adversary — the Islamic State in Syria-Iraq and Russia in Ukraine — is incapable of mounting a decisive offensive, or that any offensive it mounts can be blunted with air power. But to be successful, U.S. strategy assumes there will be coherent Ukrainian and Iraqi resistance to Russia and the Islamic State, respectively. If that doesn’t materialize or dissolves, so does the strategy.

The United States is betting on risky allies. And the outcome matters in the long run. U.S. strategy prior to World Wars I and II was to limit involvement until the situation could be handled only with a massive American deployment. During the Cold War, the United States changed its strategy to a pre-commitment of at least some forces; this had a better outcome. The United States is not invulnerable to foreign threats, although those foreign threats must evolve dramatically. The earlier intervention was less costly than intervention at the last possible minute. Neither the Islamic State nor Russia poses such a threat to the United States, and it is very likely that the respective regional balance of power can contain them. But if they can’t, the crises could evolve into a more direct threat to the United States. And shaping the regional balance of power requires exertion and taking at least some risks.

Regional Balances of Power and the Black Sea

The rational move for countries like Romania, Hungary or Poland is to accommodate Russia unless they have significant guarantees from the outside. Whether fair or not, only the United States can deliver those guarantees. The same can be said about the Shia and the Kurds, both of whom the United States has abandoned in recent years, assuming that they could manage on their own.

The issue the United States faces is how to structure such support, physically and conceptually. There appear to be two distinct and unconnected theaters, and American power is limited. The situation would seem to preclude persuasive guarantees. But U.S. strategic conception must evolve away from seeing these as distinct theaters into seeing them as different aspects of the same theater: the Black Sea.

When we look at a map, we note that the Black Sea is the geographic organizing principle of these areas. The sea is the southern frontier of Ukraine and European Russia and the Caucasus, where Russian, jihadist and Iranian power converge on the Black Sea. Northern Syria and Iraq are fewer than 650 kilometers (400 miles) from the Black Sea.

The United States has had a North Atlantic strategy. It has had a Caribbean strategy, a Western Pacific strategy and so on. This did not simply mean a naval strategy. Rather, it was understood as a combined arms system of power projection that depended on naval power to provide strategic supply, delivery of troops and air power. It also placed its forces in such a configuration that the one force, or at least command structure, could provide support in multiple directions.

The United States has a strategic problem that can be addressed either as two or more unrelated problems requiring redundant resources or a single integrated solution. It is true that the Russians and the Islamic State do not see themselves as part of a single theater. But opponents don’t define theaters of operation for the United States. The first step in crafting a strategy is to define the map in a way that allows the strategist to think in terms of unity of forces rather than separation, and unity of support rather than division. It also allows the strategist to think of his regional relationships as part of an integrated strategy.

Assume for the moment that the Russians chose to intervene in the Caucasus again, that jihadists moved out of Chechnya and Dagestan into Georgia and Azerbaijan, or that Iran chose to move north. The outcome of events in the Caucasus would matter greatly to the United States. Under the current strategic structure, where U.S. decision-makers seem incapable of conceptualizing the two present strategic problems, such a third crisis would overwhelm them. But thinking in terms of securing what I’ll call the Greater Black Sea Basin would provide a framework for addressing the current thought exercise. A Black Sea strategy would define the significance of Georgia, the eastern coast of the Black Sea. Even more important, it would elevate Azerbaijan to the level of importance it should have in U.S. strategy. Without Azerbaijan, Georgia has little weight. With Azerbaijan, there is a counter to jihadists in the high Caucasus, or at least a buffer, since Azerbaijan is logically the eastern anchor of the Greater Black Sea strategy.

A Black Sea strategy would also force definition of two key relationships for the United States. The first is Turkey. Russia aside, Turkey is the major native Black Sea power. It has interests throughout the Greater Black Sea Basin, namely, in Syria, Iraq, the Caucasus, Russia and Ukraine. Thinking in terms of a Black Sea strategy, Turkey becomes one of the indispensible allies since its interests touch American interests. Aligning U.S. and Turkish strategy would be a precondition for such a strategy, meaning both nations would have to make serious policy shifts. An explicit Black Sea-centered strategy would put U.S.-Turkish relations at the forefront, and a failure to align would tell both countries that they need to re-examine their strategic relationship. At this point, U.S.-Turkish relations seem to be based on a systematic avoidance of confronting realities. With the Black Sea as a centerpiece, evasion, which is rarely useful in creating realistic strategies, would be difficult.

The Centrality of Romania

The second critical country is Romania. The Montreux Convention prohibits the unlimited transit of a naval force into the Black Sea through the Bosporus, controlled by Turkey. Romania, however, is a Black Sea nation, and no limitations apply to it, although its naval combat power is centered on a few aging frigates backed up by a half-dozen corvettes. Apart from being a potential base for aircraft for operations in the region, particularly in Ukraine, supporting Romania in building a significant naval force in the Black Sea — potentially including amphibious ships — would provide a deterrent force against the Russians and also shape affairs in the Black Sea that might motivate Turkey to cooperate with Romania and thereby work with the United States. The traditional NATO structure can survive this evolution, even though most of NATO is irrelevant to the problems facing the Black Sea Basin. Regardless of how the Syria-Iraq drama ends, it is secondary to the future of Russia’s relationship with Ukraine and the European Peninsula. Poland anchors the North European Plain, but the action for now is in the Black Sea, and that makes Romania the critical partner in the European Peninsula. It will feel the first pressure if Russia regains its position in Ukraine.

I have written frequently on the emergence — and the inevitability of the emergence — of an alliance based on the notion of the Intermarium, the land between the seas. It would stretch between the Baltic and Black seas and would be an alliance designed to contain a newly assertive Russia. I have envisioned this alliance stretching east to the Caspian, taking in Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan. The Poland-to-Romania line is already emerging. It seems obvious that given events on both sides of the Black Sea, the rest of this line will emerge.

The United States ought to adopt the policy of the Cold War. That consisted of four parts. First, allies were expected to provide the geographical foundation of defense and substantial forces to respond to threats. Second, the United States was to provide military and economic aid as necessary to support this structure. Third, the United States was to pre-position some forces as guarantors of U.S. commitment and as immediate support. And fourth, Washington was to guarantee the total commitment of all U.S. forces to defending allies, although the need to fulfill the last guarantee never arose.

The United States has an uncertain alliance structure in the Greater Black Sea Basin that is neither mutually supportive nor permits the United States a coherent power in the region given the conceptual division of the region into distinct theaters. The United States is providing aid, but again on an inconsistent basis. Some U.S. forces are involved, but their mission is unclear, it is unclear that they are in the right places, and it is unclear what the regional policy is.

Thus, U.S. policy for the moment is incoherent. A Black Sea strategy is merely a name, but sometimes a name is sufficient to focus strategic thinking. So long as the United States thinks in terms of Ukraine and Syria and Iraq as if they were on different planets, the economy of forces that coherent strategy requires will never be achieved. Thinking in terms of the Black Sea as a pivot of a single diverse and diffuse region can anchor U.S. thinking. Merely anchoring strategic concepts does not win wars, nor prevent them. But anything that provides coherence to American strategy has value.

The Greater Black Sea Basin, as broadly defined, is already the object of U.S. military and political involvement. It is just not perceived that way in military, political or even public and media calculations. It should be. For that will bring perception in line with fast-emerging reality.

“Ukraine, Iraq and a Black Sea Strategy is republished with permission of Stratfor.”